The research targeted a heart defect, but experts say in the future the same approach can potentially prevent a whole list of inheritable diseases

By Roberto Hugo Gonzalez

As originally published by Mega Doctor News in its newsprint edition August 2017

For the first time, in decades scientists in the United States have edited the DNA of human embryos to prevent a fatal disease. An American researcher, of Russian descendants, has successfully done this with animals.

Genes cause the disease called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In other words, if you inherit a gene with a mutation on it, you’re going to make some of the proteins in your heart in an imperfect way, it’s just something you were born with.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is very common and can affect people of any age. It affects men and women equally. It is a common cause of sudden cardiac arrest in young people, including young athletes.

With this disease, it is impossible to know when your heart might fail you, never knowing if today is the day when it might go off. Some have said that it’s like you’re just walking around every day with a gun pointed at your head.

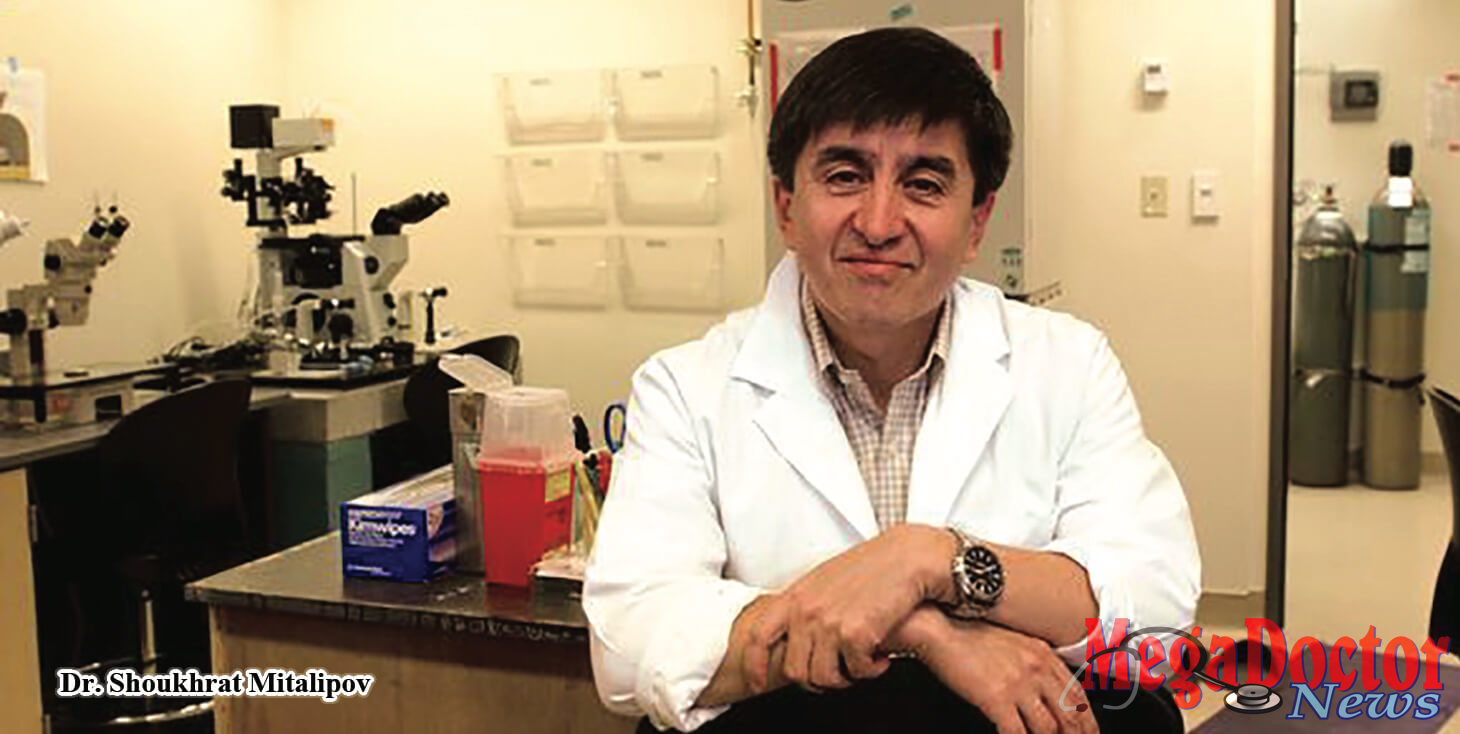

The researcher behind this breakthrough is Dr. Shoukhrat Mitalipov, Ph.D., heads the Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland Oregon. He grew up in the Soviet Union when Kazakhstan used to be of the Soviet Union; he is also an accomplished blues guitarist.

He became interested in studying the cells in embryos when he was in school in Moscow. As soon as he graduated, he came to the United States and started to work with a mentor, Dr. Keith Campbell, the scientist that helped to create the first cloned animal, Dolly the sheep/ The sheep may not be the monster imagined in a science-fiction fantasy. It is important to note that, many scientists doubted it could ever be done.

Mitalipov’s medical breakthrough is of epic proportions. Today, the United States law may block this type of medicine prevention, leaving people never knowing when their hearts will fail.

Last week a group of scientists led by Mitalipov published a breakthrough that could do just that: edit and rewrite the gene that causes this heart condition. TV commentators said, “Genetic engineering yesterday was science fiction, and today it’s reality.”

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy occurs if heart muscle cells enlarge and cause the walls of the ventricles (usually the left ventricle) to thicken. The ventricle size often remains normal, but the thickening may block blood flow out of the ventricle. If this happens, the condition is called obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Sometimes the septum, the wall that divides the left and right sides of the heart, thickens and bulges into the left ventricle. This can block blood flow out of the left ventricle. Then the ventricle must work hard to pump blood. Symptoms can include chest pain, dizziness, shortness of breath, or fainting.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy also can affect the heart’s mitral valve, causing blood to leak backward through the valve. Sometimes, the thickened heart muscle doesn’t block blood flow out of the left ventricle. This is referred to as non-obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The entire ventricle may thicken, or the thickening may happen only at the bottom of the heart. The right ventricle also may be affected.

In both obstructive and non-obstructive HCM, the thickened muscle makes the inside of the left ventricle smaller, so it holds less blood. The walls of the ventricle may stiffen, and as a result, the ventricle is less able to relax and fill with blood.

But how exactly does one edit a gene to fix that problem? According to the scientists, this recent breakthrough is an application of a new kind of tool for rewriting DNA called CRISPR, which allows for quick and easy genome editing.

CRISPR is the only complete genome editing solution designed to expedite research.

What scientists did was they created an embryo that had Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy disease, in other words, one copy of a gene from a heart protein that was faulty. They added in molecules to this embryo, which was able to zero in on the part of the gene where this mutation was that causes this disease.

Carl Zimmer is an award-winning science writer. He’s a columnist for the New York Times and the author of 13 books about science. His comments about editing the human embryo are interesting and timely. “It’s like they’re paging through an incredibly long encyclopedia until they get to a particular page. On that particular page, they get to a particular paragraph, and in that particular paragraph, they get to a particular word. They can zero in with that kind of incredible accuracy, and then they cut a section of the DNA, where scientists can insert a new piece of DNA to take its place.” This technique repairs the DNA, and in the process, it turned that gene into a normal version that lets us have regular beating hearts.

Michael Barbaro, the conductor of The Daily of the New York Times, said, “So, they’re removing a word in this deep well of language, and they’re replacing with another one.”

Zimmer pointed out that if this embryo would ever become a fully formed human, it would be a human without this terrible disease. In essence, it just would be eradicated from the biology of the baby and the adult. The scientist Dr. Mitalipov also said, “I was really shocked, so this is kind of a big moment for me to understand that we have more power in manipulating nature than we think.”

The United States has been opposed to genetic modifications in human embryos for quite a long time; they have made it very clear that they’re not going to approve clinical trials for Mitalipov’s project.

In 2016 Congress inserted a little line into the budget saying that the FDA cannot even consider an application to mitochondrial replacement therapy. Because of that, Dr. Mitalipov stated, “It’s frustrating because, you know, the goal of my career it’s to bring new revolutionary treatments. We invested so much into the science and accomplished so much progress, and now all of a sudden the FDA has told us not to pursue this work.”

For Dr. Mitalipov was important that this could be a way to cure genetic diseases. He initially became famous for all he did in research at what came to be known as three-parent-babies.

It’s an idea that bends the mind as well as the established laws of nature, one baby, with three genetic parents. As an example, 13-month-old Jessica Newels suffers from a mitochondrial disease passed down from her mother and doctors say things will get progressively worse.

It is known that we only inherit mitochondria from our mothers and if there’s mutation on one of those genes it can cause really severe diseases. Scientists combined the DNA of 2 parents with a healthy mitochondria DNA of a female donor, and that’s where you get a three-parent-baby.

So, the question is, what happened with that research of this three-parent-baby concept? It worked on mice, and so then Mitalipov moved onto monkeys which are closer to humans. Two baby monkeys were born and cured of their mitochondrial disease.

The success of his research gave him and others a certain boost to say, “okay let’s go to government agencies and ask for permission to apply this technology in humans.” In the United States, it’s just a very different story, the answer to that was a big NO. The United Kingdom opened its doors, and they have gone forth with approving it and moving forward with this, full steam ahead with lots of regulations.

Dr. Mitalipov said, “I understand that you need to draw a line, what’s permissible what’s not. We don’t want a neglected use, but what we’re asking is let us test it. It needs to be tested in clinical settings.”

Zimmer said, “Even the scientists themselves have been stunned by how fast they’ve been hitting these successes and scientists are making an effort to try and make the rest of us aware of what CRISPR is and what the potential benefits and ethical issues are.”

Dr. Mitalipov also said, “I don’t think, you know, this technology can’t be stopped at this stage, and I believe this is going to be the future, and an initial interest of every country, the United States has just to reconsider their policies.”

Zimmer said, “It’s really hard for me to look into the future on this one, because when you look at our past experiences, sometimes things go from being really shocking and hard to find them normal.” He continued, “Vitro Fertilization in the 1960’s was considered very scandalous, and most people were against it.” Today, he pointed out it’s extremely common, regulated, it’s licensed in the US, and it’s just a familiar part of life. “So, the question is will CRISPR become a familiar part of life 50 years from now? I really don’t know,” Zimmer said.

Barbaro said, “So, you say this is truly revolutionary in the world of science and medicine. Why is it such a big deal?

Zimmer responded, “For decades, the scientists wanted to do this. To be able to fix genetic diseases by manipulating embryos. In other words, it’s possible that if you took one of these embryos, and implanted it in a surrogate mother, the embryo will develop into a normal human being, healthy despite having edited DNA, and, in fact will not carry the disease that they have inherited, and not only that, but will not pass it down to their descendants.”

Also, Dr. Mitalipov said, “I know in the future this kind of treatments will become routine probably a million children will be cured of these inheritable conditions and that’s what nature is every day.” He continued, “I didn’t want to be just a scientist or be the best of the best, I wanted to be number 1, and then hopefully show everybody that they’re wrong. 100 years from now they’re going to remember “Yeah that’s Mitalipov, he developed it.”

The U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report notes that many inherited diseases can be prevented by selecting healthy embryos for in-vitro fertilization, and that embryo editing might only be justified if it presents the only option for a couple to have a healthy biological child. Congress has meanwhile prohibited the U.S. Food and Drug Administration from reviewing applications for clinical trials involving embryo editing. MDN