Mega Doctor News

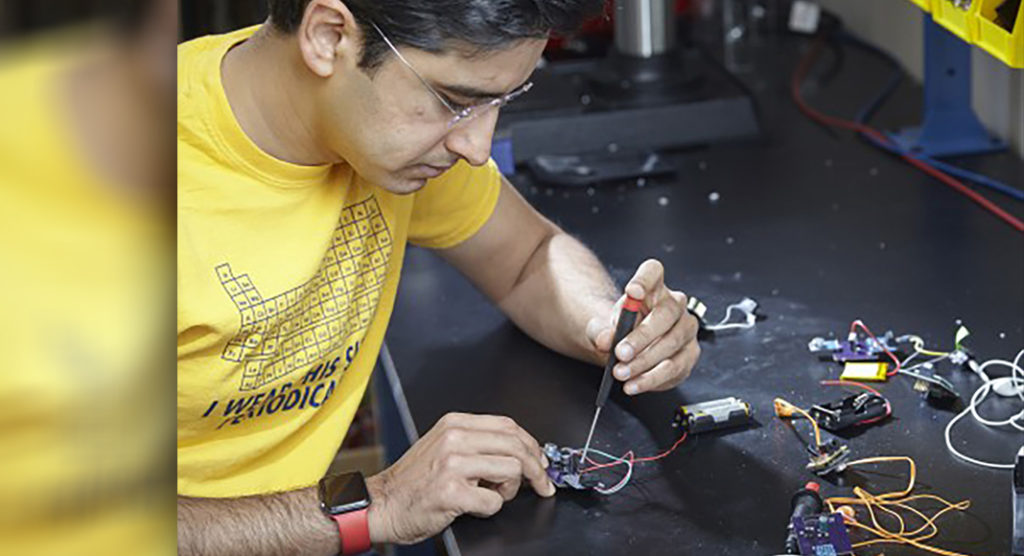

Newswise — Using a device that could be built with a dollar’s worth of open-source parts and a 3D-printed case, researchers want to help the hundreds of millions of older people worldwide who can’t afford existing hearing aids to address their age-related hearing loss.

The ultra-low-cost proof-of-concept device known as LoCHAid is designed to be easily manufactured and repaired in locations where conventional hearing aids are priced beyond the reach of most citizens. The minimalist device is expected to meet most of the World Health Organization’s targets for hearing aids aimed at mild-to-moderate age-related hearing loss. The prototypes built so far look like wearable music players instead of a traditional behind-the-ear hearing aids.

“The challenge we set for ourselves was to build a minimalist hearing aid, determine how good it would be and ask how useful it would be to the millions of people who could use it,” said M. Saad Bhamla, an assistant professor in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “The need is obvious because conventional hearing aids cost a lot and only a fraction of those who need them have access.”

Details of the project are described September 23 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Age-related hearing loss affects more than 200 million adults over the age of 65 worldwide. Hearing aid adoption remains relatively low, particularly in low-and-middle income countries where fewer than 3 percent of adults use the devices – compared to 20 percent in wealthier countries. Cost is a significant limitation, with the average hearing aid pair costing $4,700 in the United States and even low-cost personal sound amplification devices – which don’t meet the criteria for sale as hearing aids – priced at hundreds of dollars globally.

Part of the reason for high cost is that effective hearing aids provide far more than just sound amplification. Hearing loss tends to occur unevenly at different frequencies, so boosting all sound can actually make speech comprehension more difficult. Because decoding speech is so complicated for the human brain, the device must also avoid distorting the sound or adding noise that could hamper the user’s ability to understand.

Bhamla and his team chose to focus on age-related hearing loss because older adults tend to lose hearing at higher frequencies. Focusing on a large group with similar hearing losses simplified the design by narrowing the range of sound frequency amplification needed.

Modern hearing aids use digital signal processors to adjust sound, but these components were too expensive and power hungry for the team’s goal. The team therefore decided to build their device using electronic filters to shape the frequency response, a less expensive approach that was standard on hearing aids before the processors became widely available.

“Taking a standard such as linear gain response and shaping it using filters dramatically reduces the cost and the effort required for programming,” said Soham Sinha, the paper’s first author, who was born in semi-rural India and is a long-term user of hearing aid technology.