The Texas Tribune

BY KAREN BROOKS HARPER / THE TEXAS TRIBUNE

El Paso resident Carlos Martinez was relieved in June when the number of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths were dropping in his community.

Martinez, 25, started going to restaurants for the first time in months, seeing friends and going out again after being careful for more than a year.

Then the highly contagious delta variant began to take hold across Texas and the rest of the nation in July, and the numbers started to climb again across the state.

Martinez, who is vaccinated, said he went back into isolation to help reduce the spread of the virus in El Paso, where COVID-19 killed so many people late last year that the county had to use inmates to help with the overflow of bodies at the morgue.

But while delta raged through most of the state’s 254 counties in July and August, breaking records and overwhelming hospitals in both rural conservative areas and sprawling liberal metros, El Paso — with one of the highest vaccination rates in the state — has been relatively unscathed by the most recent surge.

“We held our breath after July Fourth, but we didn’t see the increase we thought we’d see in terms of hospitalizations,” said Martinez, a local government employee.

While some other metro areas like Austin reported record high numbers of COVID-19 patients in their area hospitals just last month, and while statewide hospitalizations came close to eclipsing the January peak of 14,218, El Paso-area hospitals, which serve nearly a million West Texas residents, haven’t come close to their previous highs.

El Paso’s peak for COVID-19 hospitalizations was just over 1,100 in mid-November, said Wanda Helgesen, director of BorderRAC, the state’s regional advisory council for local hospitals.

On Thursday, the number of people hospitalized for COVID-19 in El Paso was 127.

In fact, the city’s daily hospitalization numbers haven’t broken 200 since March, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services. Hospitals are seeing an increase in patients, have occasionally seen their ICUs fill up and are having the same staffing problems as the rest of the state, she said, but have so far been able to handle the uptick.

Most of the pressure is related to non-COVID patients, many of whom had been waiting to get treatment for other problems, she said.

“We do have a surge of patients but not to the extent that other parts of Texas are having,” she said.

Helgesen and others say much of the credit can be attributed to the area’s high vaccination rate, widespread compliance with masking and social distancing, and a strong partnership among local community and health care leaders.

“It is amazing,” Helgesen said. “It is absolutely a credit to our community. I really think it was an all-out effort.”

The share of COVID-19 tests in El Paso that come back positive is hovering around 6%, while the statewide positivity rate is three times that at 18%.

And while COVID-19 patients, most of whom are unvaccinated, took up more than 30% of hospital capacity in some areas and more than 20% statewide last week, in El Paso they accounted for only 7% of patients in local hospitals.

For a city with one of the state’s highest per-capita COVID-19 death counts, the numbers present a rare glimmer of good news for the traumatized residents of this West Texas border city.

“Compared to the rest of Texas, we’re in heaven,” said Gabriel Ibarra-Mejia, assistant professor of public health at the University of Texas-El Paso. “That doesn’t mean we are free from COVID, but we’re doing much, much better than most of the rest of the state. The numbers don’t lie.”

Civic and health leaders say they aren’t ignoring one important fact: El Paso’s surges have been weeks behind the rest of the state throughout the pandemic, so it’s possible that the region’s own delta-fueled spike could still be ahead.

“We aren’t letting our guard down,” Helgesen said.

El Paso Mayor Oscar Leeser, who lost his mother and brother to COVID during the winter surge, said the reason the city and county have enacted recent mask mandates, in defiance of Gov. Greg Abbott’s ban on them and in spite of lower numbers, is because the potential for another surge is still real.

“We do worry and we want to make sure that we don’t have any spikes,” he said. “You always want to be proactive and you always want to be prepared.”

Sense of community helps COVID response

El Paso was in the national spotlight in November when it had one of the highest COVID-19 death rates in the country.

Images of county jail trustees in black-and-white stripes moving body bags into eight mobile morgue trucks outside the understaffed medical examiner’s office were a shocking illustration of the heavy toll the virus took on the community.

During the fall, the number of hospitalized coronavirus patients in El Paso shot up nearly tenfold between September and November, at a time when the numbers dropped and restrictions were relaxed in most other parts of the state.

El Paso’s COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations remained relatively high well into the early springtime while the rest of the state was experiencing a decline as vaccines became available.

Today, El Pasoans may be taking the delta surge more seriously than residents in other areas that were less hard hit because of that traumatic time, said Chris Van Deusen, spokesperson for the Texas Department of State Health Services.

“El Paso experienced one of the biggest crises of the pandemic with hospitals absolutely overrun by COVID patients last year, and the communal memory of that period and the measures that helped the city and region cope may be helping people take the current situation more seriously,” he said.

There are several other factors that likely play into El Paso’s relative success at keeping the delta variant at bay and people out of the hospital, state and local health officials and residents say.

There may be a high level of natural immunity among local residents, which medical experts say appears to keep COVID-19 sufferers out of the hospital in the slight chance they are reinfected, health experts say.

There has been wide acceptance of the monoclonal antibody treatments, which Helgesen said kept at least 300 people out of hospitals during the last surge and, because the area never closed its regional infusion center as other areas did when numbers went down in the spring, is likely keeping people out of hospitals now, too.

The city’s geography is also a factor: It is hundreds of miles from the nearest major population center, and it borders New Mexico, which has one of the highest vaccination rates in the nation at 61% fully vaccinated.

And the Walmart mass shooting two years ago, in which 23 people were killed on Aug. 3, 2019, contributed to an increased sense of community and empathy that tends to lend itself to widespread compliance with masking and vaccinations, said local resident Steven Wysocki.

“That El Paso Strong thing has been resonating ever since the Walmart shooting,” he said. “So that’s another thing. ‘Let’s protect our community.’ It’s on a personal level. It’s a strong sense of family and community responsibility. Even though El Paso’s population is close to a million, we’re still a small town.”

Van Deusen said the tragedy likely engendered trust in the local pandemic response.

“There does seem to be a sense of community and trust in local leaders and public health … that can go a long way to helping promote a cohesive community response to a crisis,” he said.

When Abbott lifted statewide mask mandates and business limits in March, civic leaders in El Paso begged their residents to keep wearing masks, and most businesses continued to limit their services voluntarily throughout the spring, Leeser said.

Wysocki, a 51-year-old disabled Army veteran, says most people seem to be taking the latest statewide surge seriously.

“Any store I go to, every place I go, people have got their mask and they put it on,” he said.

El Paso among most vaccinated counties in Texas

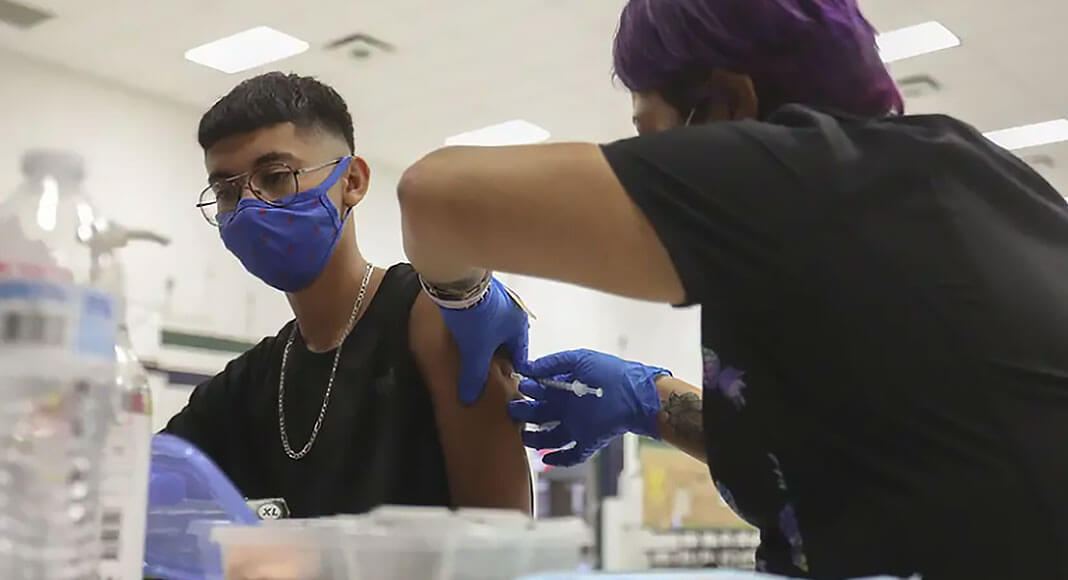

But it’s the high vaccination rate in El Paso that most are saying is the main factor in the community’s relative success at tamping down the impact of the delta surge.

Nearly 62% of all El Paso’s residents are fully vaccinated, compared with 49% statewide. Almost 97% of all El Pasoans age 65 and older, the age group at the highest risk of hospitalization and death, have had at least one shot.

By contrast, only about one-third of residents in the Panhandle and East Texas are fully vaccinated.

“We’ve done a really, really good job of making sure our community was vaccinated, and that’s made a huge difference,” Leeser said. “And when we talk about ‘we,’ it’s not just the city of El Paso. It’s the county, the county judge, University Medical Center, the private providers, everyone in the area. We all rallied together, and it’s been one continuous message we’ve been getting out to the community.”

The COVID-19 vaccines do not guarantee that recipients won’t get the virus, but they are highly effective at keeping infected patients out of the hospital and almost 100% effective at preventing death from the virus.

Wysocki got his vaccine as soon as he could, as did the rest of his family.

He caught the virus several months before the vaccine came out and was bedridden for several days, an episode he said motivated his whole family.

“Everyone in our family immediately got the shots [when they were available],” Wysocki said. “No one wanted to go through that.”

El Paso County Judge Ricardo Samaniego said a big part of the success is because El Paso residents are used to looking out for each other.

“We know how to do this,” he said. “We know how to come together. We’ve done it before, and we’re going to do it again.”

Chris Essig contributed to this report.